Your Right to Choose Is Sacred

- Tuesday, 11 October 2022 14:43

- Last Updated: Tuesday, 11 October 2022 14:49

- Published: Tuesday, 11 October 2022 14:43

- Canto Amanda Kleinman

- Hits: 2562

(This Kol Nidre sermon was delivered by Cantor Amanda Kleinman at Westchester Reform Temple)

(This Kol Nidre sermon was delivered by Cantor Amanda Kleinman at Westchester Reform Temple)

I’d like to begin my sermon tonight by giving a plug to someone else’s sermon. Last spring, Emily Levine, a member of our tenth grade Confirmation class, delivered an eloquent and insightful D’var Torah advocating for reproductive rights from a Jewish perspective. Emily began by saying, “I’m going to be completely honest. When I realized during Confirmation that I wanted to talk about abortion at temple, I wasn’t sure how the clergy was going to respond. I had a whole speech planned in case they told me it was ‘too controversial.’”

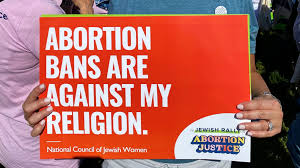

As a woman, as a mother, and as a Jew, it was painful for me to hear a young person question whether temple was the appropriate place to stand up for women’s rights. Painful, but not surprising. In fact, every year when I teach this topic in Confirmation, I begin by asking what students think the Jewish tradition has to say about abortion. Without fail, they assume that Judaism prohibits it. The reason I ask the question in the first place is because, for most of my life, I assumed that the protests I saw when I drove past Planned Parenthood, you know the ones - religious leaders speaking passionately into megaphones flanked by signs quoting Biblical verses - represented the viewpoint of all religious traditions, including my own. It wasn’t until I was studying to be a cantor that I learned that Judaism actually affirms a woman’s right to choose.

The idea that our Jewish tradition would sanctify our ability to make our own choices can feel surprising, if not unsettling. Religion is supposed to make our choices for us, right? Religion is supposed to offer us moral clarity. As the product of an Orthodox Jewish day school, and having been raised, at least in part, in an Orthodox community, I understand firsthand the feeling that religion is supposed to offer us firm answers, certainty, and direction.

Baptist minister Katey Zeh, who also serves as the CEO of the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, questions this tendency to look to religion for absolutes. She reflects: “I grew up in a . . . conservative, white, Evangelical church, so I am very familiar with a theological framework that is cut and dry, that things are this or they’re not, that God is this or God isn’t. There is a certain comfort that if I simply follow these rules, then my life will be wonderful. I subscribed to that for a long time until I had experiences that required me to do a lot of soul searching around what it means to be a faithful person with a theological framework that allows for nuance and complexity.”

In fact, Judaism is all about nuance and complexity. The Jewish tradition has never been one of absolutes. Look at the Talmud, the seventh century rabbinic text that became the foundational building block of Jewish law. The Talmud preserves thousands of pages of rabbinic arguments and counter-arguments across centuries. When the rabbis do not reach consensus, the Talmud’s redactors conclude the argument simply with the word “Teiku,” or “Let it stand” as an unresolved issue. In one particularly powerful example, after three years of especially rancorous debate between the house of Hillel and the house of Shammai, a heavenly voice descends to announce, “Eilu v’eilu divrei Elohim chaim heim,” Both viewpoints are words of the living God.

Our Reform movement goes even a step beyond valuing debate and discussion; we uphold the value of individual autonomy and sanctify it as a moral obligation. In 1937, our Reform rabbis declared, “As a child of God, man is endowed with moral freedom.” Forty years later, they affirmed, “Reform Jews are called upon to . . . to exercise their individual autonomy, choosing and creating on the basis of commitment and knowledge.” In other words, for us as Reform Jews, autonomy is not only a privilege, or even a right; it takes on the status of mitzvah, of sacred responsibility.

If only our current Supreme Court agreed. Thirty years ago, in Casey v. Planned Parenthood, the Supreme Court made the bold statement that “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” A woman’s ability to make “intimate and personal choices” was regarded as “central to personal dignity and autonomy.” This summer’s Dobbs decision, however, rolled back the clock on women’s autonomy almost fifty years, to a time when a woman couldn’t get a credit card without her husband’s signature on the application, and when some states still systematically excluded women from juries. The justices wrote in the Dobbs decision, “These attempts to justify abortion through appeals to a broader right to autonomy and to define one’s ‘concept of existence’ prove too much. Those criteria, at a high level of generality, (and they actually wrote this) could license fundamental rights to illicit drug use, prostitution, and the like. None of these rights has any claim to being deeply rooted in history.”

I beg to differ. My history has always upheld the sanctity of life AND given priority to the life and well-being of the mother. Over a thousand years ago, the Talmud taught: “The fetus is the thigh of the mother,” and elsewhere, “The fetus is her body,” making clear that, in Judaism, the health and wellbeing of the pregnant woman takes precedence over that of the fetus. When the mother’s life is threatened, Judaism actually requires termination of the pregnancy. Even when the physical health of the mother is not at stake, our tradition gives us space to consider each pregnant woman’s unique circumstances, in many cases permitting abortion when the primary concern is a woman’s emotional well-being. And I’m not talking only about our liberal Reform tradition; in fact, these texts and interpretations come straight out of Orthodox Jewish practice.

It is, nevertheless, important to note that our traditional texts were written by men. Halakha, the traditional Jewish legal system, leaves something to be desired when it comes to women’s autonomy, generally giving the authority to sanction an abortion to a male rabbi. My colleague, Rabbi Hannah Goldstein, who delivered a beautiful sermon on this topic over Rosh Hashanah, calls it “fighting patriarchy with patriarchy.” Yet, I am proud to be part of a religious tradition that gives real consideration to women’s needs, and I am especially proud to be part of a Reform movement that sanctifies “the legal right of a woman to act in accordance with the moral and religious dictates of her conscience.” In Reform Judaism, the final authority about how we live our Jewish values does not reside with the cantor or the rabbi, or some other governing body or institution. It resides within each of us.

As I prepared this sermon, I had the opportunity to speak with a number of you, our congregants, who are affected by this threat to reproductive choice. I was so grateful for your candor. I spoke with Lisa Eisenstein who, as a young person, was so aghast to learn that women could be denied access to basic health care, that she became a champion of reproductive freedom and served for many years on the board of Planned Parenthood, only to see much of what she worked so hard to protect erased. I spoke with Dr. Susan Klugman, a national leader in the field of reproductive genetics, who told me that her colleagues in other states are reluctant to share reproductive options with their patients for fear of going to jail. A few of you told me stories of your own abortions, each of you grateful for the choice that was available to you, and also horrified that, for many, that same choice is unavailable today.

At a time in my life when I needed to consider my reproductive choices, I consulted my then doctor who came from a devout Catholic background. Years earlier, we had bonded over being people of faith; delighted when I shared that I was a cantor, she told me that her own mother had once been a nun, and that she thought we had a lot in common. When I asked her my questions, I sensed her inner struggle. If we were both people of faith, how could my values be so different from hers? At my next visit, she surprised me when she said that she intended to support me, regardless of my choice. While I cannot know exactly what she was thinking, I like to imagine that she decided to trust me to make a decision guided by my own values, a decision that would be between me and my God. It was a tremendously powerful moment of personal validation, not only of being entrusted with my own choices, but of being supported through those choices, even when the person offering the support might disagree with my decision.

As we stand on the precipice of a new year, the first in a long while that doesn’t guarantee a woman’s right to choose here in America, let us turn to the words of the prayer for which this evening’s service is named, Kol Nidre. The Kol Nidre prayer reads: “All vows - resolves and commitments, vows of abstinence and terms of obligation, sworn promises and oaths of dedication - that we take upon ourselves from this Day of Atonement until next Day of Atonement, let all of them be discarded and forgiven, abolished and undone; they are not valid and they are not binding.”

A little-known fact: the rabbis tried to get rid of the Kol Nidre prayer for literally thousands of years, fearing that a statement nullifying future vows plays into stereotypes that Jews can’t be counted on to fulfill their promises. Rabbi David Stern, son of WRT’s beloved Rabbi Jack Stern, of blessed memory, and who, by the way, gave me my own entry point into Reform Judaism as my family’s rabbi in Dallas, offers another interpretation. He writes, “Kol Nidre grants us the gift of sacred uncertainty, the chance to begin this new year with a sense of what we do not know, rather than a narrow certainty about what we do.” In other words, the authors of the prayer recognized that our tradition cannot provide us with all the answers; instead, Kol Nidre empowers us to make the best choices we can, and the comfort of knowing that God will forgive us if we transgress. This Yom Kippur, let us pray for the confidence to make our own choices, and for the humility to support the choices of others.

And so, to you, Emily, I say thank you. I am so glad you were brave enough to ask the “controversial” question. Why make assumptions when we can just ask? Temple is exactly the place to grapple with difficult questions, so that you can come away with your own understanding, rooted in our community’s shared values. Clearly, we haven’t yet shouted it from the rooftops, so I’ll shout it from this bima on the holiest day of the year: your religious tradition, your temple, and your clergy consider your right to choose to be sacred.